The Apache HTTP server and NGINX are the two most popular open source web servers powering the Internet today. When Igor Sysoev began working on NGINX over 10 years ago, no one expected that the project he created for the purpose of accelerating a large Apache‑based service would grow to have the influence it has now.

Apache HTTP server is a solid platform for almost any web technology developed over the last 20 years, but time is showing that the architectural decisions made when the code was first laid down are becoming limiting factors in its suitability for modern web demands.

In this article, I’ll share my perspective on these changes and limitations, and explain how a modern web developer can respond. I write this as a very early user of Apache (and of NCSA’s httpd before that), as someone who wrote CGI scripts in bash and Perl before PHP was anywhere near mainstream, and as a one‑time software engineer at Zeus, one of the very first event‑driven web servers to challenge the Apache model of doing things. My belief is absolutely not that Apache is unfit for purpose, but that in the face of modern web applications, it is now dated and needs support in order to function effectively.

The Key to Apache’s Early Success

Apache was the backbone of the first generation of the World Wide Web, becoming the industry standard for web serving almost as soon as it debuted in 1995. It was created at a time when the World Wide Web was still a novelty. Traffic levels were low, web pages were simple, bandwidth was constrained and expensive, and CPU was relatively cheap. There was a huge thirst in the early community to innovate with new technologies, and Apache was the platform of choice.

Architectural Simplicity

The simplicity of Apache’s architectural model was key to its early success. At that time, many network services were triggered from a master service called inetd; when a new network (TCP) connection was received, inetd would fork( ) and exec( ) a Unix process of the correct type to handle the connection. The process read the request on the connection, calculated the response and wrote it back down the connection, and then exited.

Apache took this model and ran with it. The biggest downside was the cost of forking a new httpd worker process for each new connection, and Apache developers quickly adopted a prefork model in which a pool of worker processes was created in advance, each ready and willing to accept one new HTTP connection.

When a prefork Apache web server received an HTTP connection, one of the httpd worker processes grabbed and handled it. Each process handled one connection at a time, and if all of the processes were busy, Apache created more worker processes to be ready for a further spike in traffic.

Easy to Develop, Easy to Innovate

The isolation and protection afforded by the one‑connection‑per‑process model made it very easy to insert additional code (in the form of modules) at any point in Apache’s web‑serving logic. Developers could add code secure in the knowledge that if it blocked, ran slowly, leaked resources, or even crashed, only the worker process running the code would be affected. Processing of all other connections would continue undisturbed.

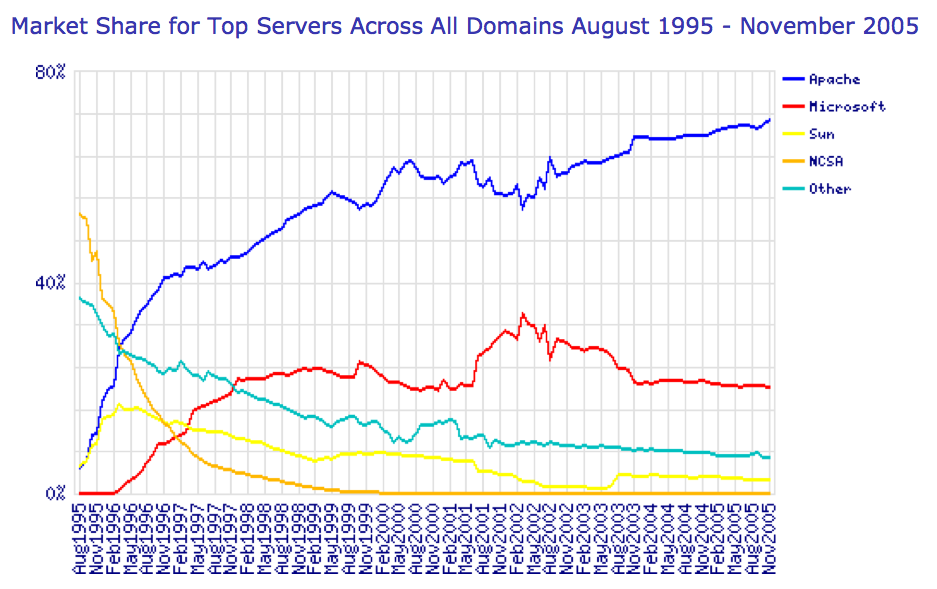

Apache quickly became the dominant web server on the early World Wide Web. Its adoption at websites grew steadily, peaking at over 70% market share at the end of 2005.

Challenged by the Growth of the World Wide Web

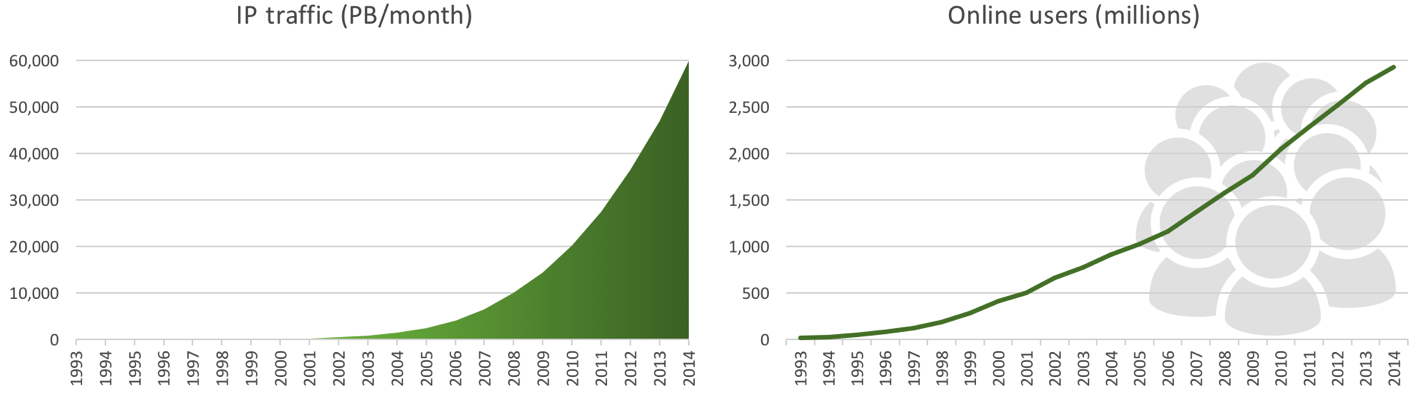

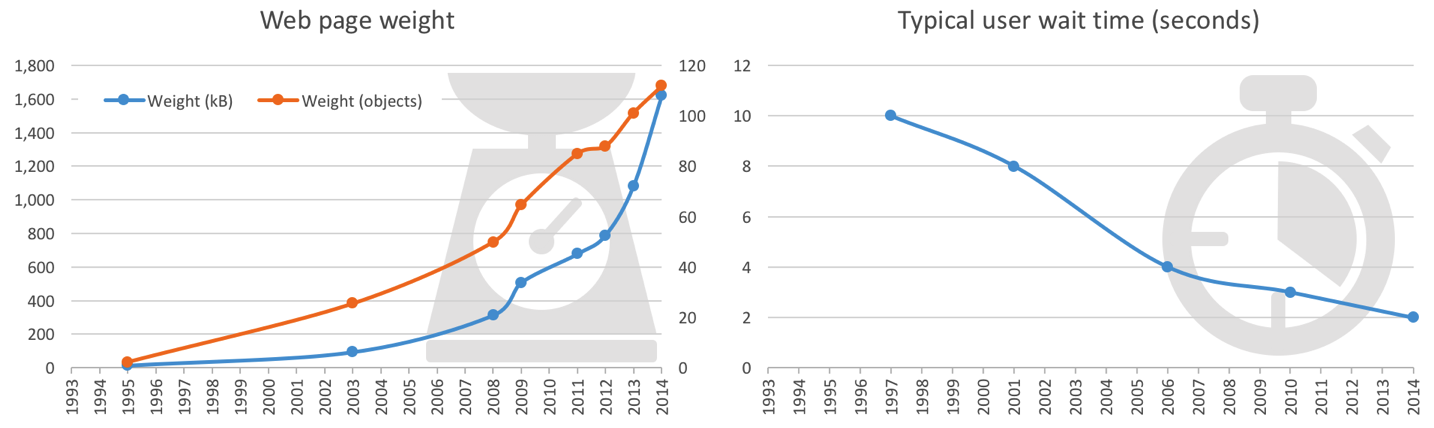

Over the past 20 years, there has been explosive growth in the volume of traffic and the number of users on the World Wide Web.

At the same time, the weight of web pages (the size and number of components the web browser has to fetch to render a page) has grown steadily, and users have become less and less patient about waiting for web pages to load.

(For more details about these changes, check out the list of resources for Internet statistics at the end of this post.)

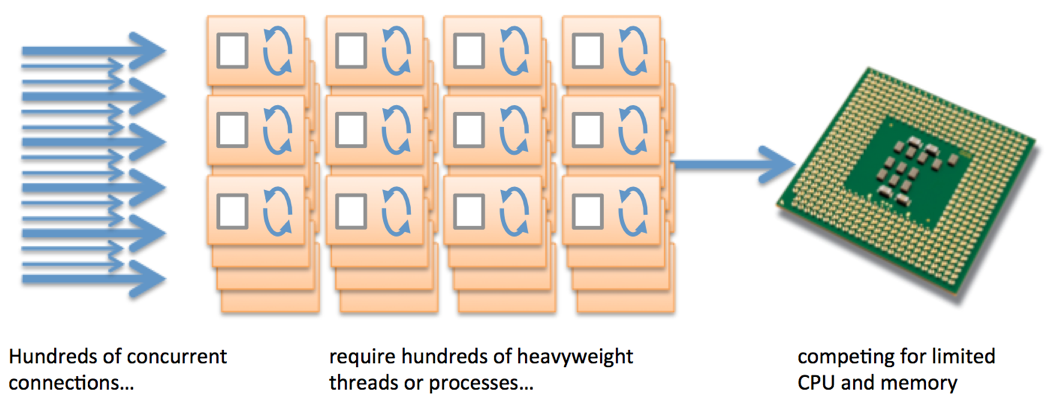

All of these changes presented a real challenge to Apache’s process‑per‑connection model, which did not scale well in the face of high traffic volume and heavy pages (more embedded resources requiring more HTTP requests).

Web Clients Greedily Use Resources

To decrease page‑rendering time, web browsers routinely open six or more TCP connections to a web server for each user session so that resources can download in parallel. Browsers hold these connections open (a practice called HTTP keepalive) for a period of time to reduce delay for future requests the user might make during the session. Each open connection exclusively reserves an httpd process, meaning that at busy times, Apache needs to create a large number of processes.

Running lots of processes consumes lots of memory. Excessive consumption results in thrashing and large numbers of context switches, which can slow the web server to a crawl.

Admins Fought Against Clients to Recover Resources

To mitigate the performance problems of the prefork Apache server, admins were encouraged to adopt two measures. They limited the maximum number of httpd processes (typically to 256) to avoid exhausting server resources; as a result, when the number of concurrent TCP connections exceeds the number of processes, new connections are stalled indefinitely. Admins also disabled keepalive connections or reduced their duration, in order to free up httpd processes more quickly.

Both of these measures have a detrimental effect on the user experience, causing web pages to load more slowly and less reliably.

The Apache Team Implemented Alternative MPMs

To improve portability and scalability on some platforms, Apache’s core developers created two additional processing models (called multi‑processing modules, or MPMs).

The worker MPM replaced separate httpd processes with a small number of child processes that ran multiple worker threads and assigned one thread per connection. This was helpful on many commercial versions of Unix (such as IBM’s AIX) where threads are much lighter weight than processes, but is less effective on Linux where threads and processes are just different incarnations of the same operating system entity.

Apache later added the event MPM (not to be confused with NGINX’s event‑driven architecture), which extends the worker MPM by adding a separate listening thread that manages idle keepalive connections once the HTTP request has completed.

Apache’s Heavyweight, Monolithic Model Has Its Limits

These measures go some way to improving performance, but the monolithic one‑server‑does‑all model that was key to the early success of Apache has continued to struggle as traffic levels increase and web pages become richer and richer. Performance in lab benchmarks is often not replicated in live production deployments at busy websites, and tuning Apache to cope with real‑world traffic is a complex art. Somewhat unfairly, Apache has gained a reputation as a bloated, overly complex, and performance‑limited web server that can be exploited by slow denial‑of‑service (DoS) attacks.

Introducing NGINX – Designed for High Concurrency

NGINX was written specifically to address the performance limitations of Apache web servers. It was created in 2002 by Igor Sysoev, a system administrator for a popular Russian portal site (Rambler.ru), as a scaling solution to help the site manage greater and greater volumes of traffic. It was open sourced in October 2004, on the 47th anniversary of the launch of Sputnik.

NGINX can be deployed as a standalone web server, and as a frontend proxy for Apache and other web servers. This drop‑in solution acts as a network offload device in front of Apache servers, translating slow Internet‑side connections into fast and reliable server‑side connections, and completely offloading keepalive connections from Apache servers. The net effect is to restore the performance of Apache to near the levels that administrators see in a local benchmark.

NGINX also acts as a shock absorber, protecting vulnerable Apache servers from spikes in traffic and from slow‑connection attacks such as Slowloris and slowhttprequest.

The Secret’s in the Architecture

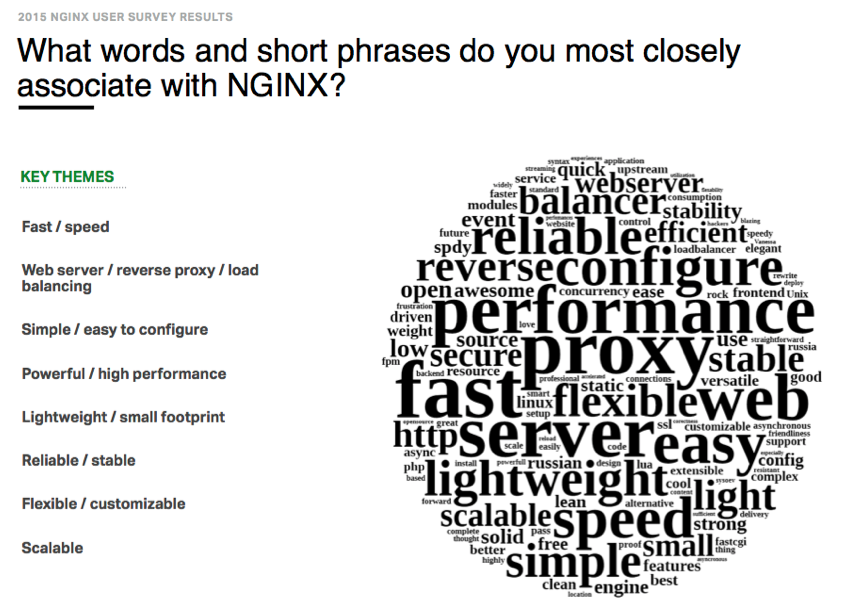

The performance and scalability of NGINX arise from its event‑driven architecture. It differs significantly from Apache’s process‑or‑thread‑per‑connection approach – in NGINX, each worker process can handle thousands of HTTP connections simultaneously. This results in a highly regarded implementation that is lightweight, scalable, and high performance.

A downside of NGINX’s sophisticated architecture is that developing modules for it isn’t as simple and easy as with Apache. NGINX module developers need to be very careful to create efficient and accurate code, without any resource leakage, and to interact appropriately with the complex event‑driven kernel to avoid blocking operations. As a result, the success of the NGINX project has rested heavily on the core development team employed by NGINX, Inc., the company founded by Igor Sysoev in 2011 to ensure the future of the NGINX Open Source.

The announcement at nginx.conf 2015 of future support for dynamic modules marks the next stage of a third‑party developer ecosystem, with fewer barriers to entry than the earlier compile‑in architecture.

Editor – NGINX Plus Release 11 (R11) and NGINX Open Source 1.11.5 introduce binary compatibility for dynamic modules, including support for compiling custom and third‑party modules.

NGINX and Apache – A Good Starting Point

For many application types, NGINX and Apache complement each other well, so it’s often more apt to talk about “NGINX and Apache” instead of “NGINX vs. Apache”. A very common starting pattern is to deploy NGINX Open Source as a proxy (or NGINX Plus as the application delivery platform) in front of an Apache‑based web application. NGINX performs the HTTP‑related heavy lifting – serving static files, caching content, and offloading slow HTTP connections – so that the Apache server can run the application code in a safe and secure environment.

NGINX provides all of the core features of a web server, without sacrificing the lightweight and high‑performance qualities that have made it successful, and can also serve as a proxy that forwards HTTP requests to upstream web servers (such as an Apache backend) and FastCGI, memcached, SCGI, and uWSGI servers. NGINX does not seek to implement the huge range of functionality necessary to run an application, instead relying on specialized third‑party servers such as PHP‑FPM, Node.js, and even Apache.

“Apache is like Microsoft Word. It has a million options but you only need six. NGINX does those six things, and it does five of them 50 times faster than Apache.”

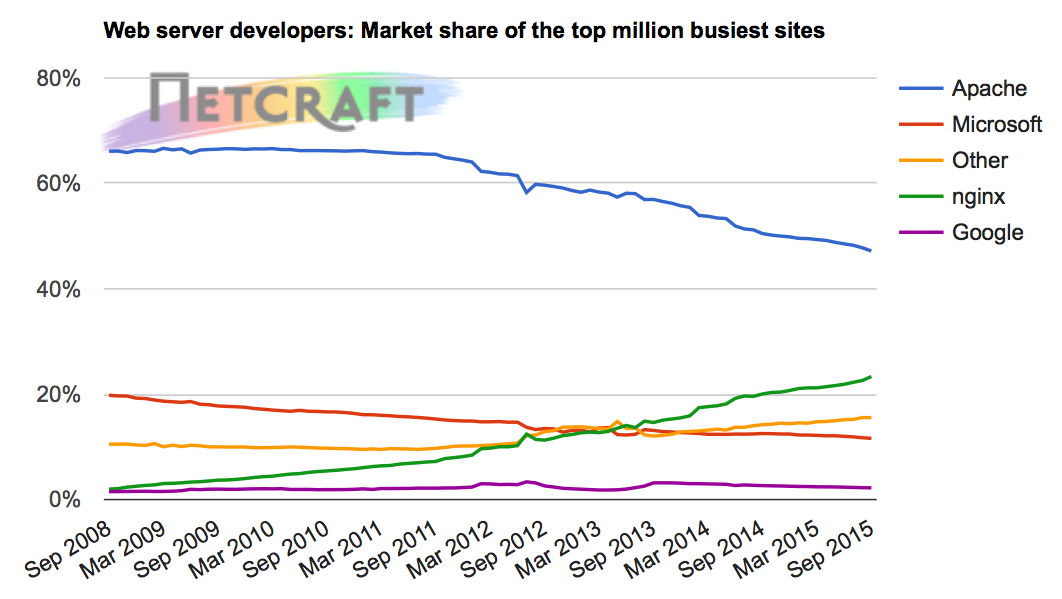

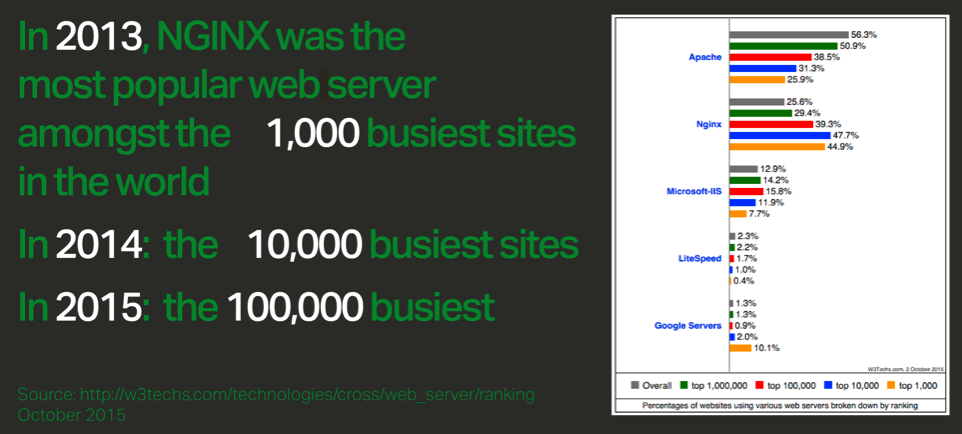

For this reason, the market share of NGINX has grown steadily over recent years, as reported in surveys from Netcraft and W3Techs.

(Note that these surveys just detect the software that handles incoming Internet traffic and stamps outgoing responses with an identifying Server header. They don’t offer much insight into what software and platforms lie within an application.)

And so emerged the architectural pattern of running NGINX at the frontend to act as the accelerator and shock absorber, and whatever technology is most appropriate for running applications at the backend.

Modern Web Applications are Very Different From the LAMP Stacks of the Past

You might have heard the buzz around containers, microservices, and lightweight application frameworks such as Node.js and Python/uWSGI.

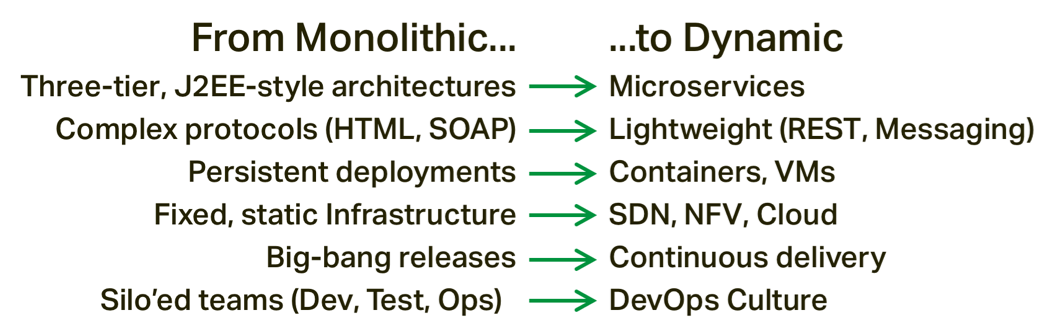

We are seeing significant changes in the ways that modern web applications are built:

Underlying these changes is a desire to achieve faster time‑to‑market for new web applications and features, by moving away from heavy, monolithic architectures to more loosely coupled, distributed architectures. Continuous delivery is the fundamental driving force behind this shift.

NGINX Delivers Microservices Applications

Containerized and microservices applications require a stable and reliable frontend that conceals the complexity and ever‑changing nature of the application behind it.

To forward HTTP requests to upstream application components, the frontend needs to provide termination of HTTP, HTTPS, and HTTP/2 connections, along with “shock‑absorber” protection and routing. It also needs to offer basic logging and first‑line access control, implement global security rules, and offload HTTP heavy lifting (caching, compression) to optimize the performance of the upstream application.

This is where NGINX and NGINX Plus come into their element, providing these twelve features (among others) that make them ideal for microservices and containers:

- Single, reliable entry point

- Serve static content

- Consolidated logging

- SSL/TLS and HTTP/2 termination

- Support multiple backend apps

- Easy A/B testing

- Scalability and fault tolerance

- Caching (for offload and acceleration)

- GZIP compression

- Zero downtime

- Simpler security requirements

- Mitigate security and DDoS attacks

Use NGINX to Give Consistency Within Each Containerized Service

Modern, distributed web applications can use a mix of diverse application components, and it’s not uncommon for them to combine a number of different technologies and platforms. The common requirement is that each component be lightweight and scalable, suitable for deploying in containers on a resource‑constrained multitenant server.

Many containers don’t need an embedded web server. They deliver their service using the framework’s own simple HTTP frontend, or using protocols such as FastCGI or uWSGI. In some cases, however, a robust and lightweight web server is required – for example, for efficiency, logging, security, monitoring, or additional functionality. The lightweight nature of NGINX makes it a much better choice to insert in a container than the Apache monolith.

Conclusion

Apache and NGINX both have their place, and NGINX is clearly in the ascendency. Your requirements and experience might lead you to chose one or both, or even a different path.

A monolithic architectural framework was sound practice when Apache was new and fresh, but app developers are finding that such an approach is no longer up to the task of delivering complex applications at the speed their businesses require. Microservice architecture is emerging as the wave of the future for web apps and sites, and NGINX is perfectly poised to assume its place in that architecture as the ideal application delivery platform for the modern Web.

Resources for Internet Statistics

Cisco’s Visual Networking Index (links to historical reports and forecasts on dozens of statistics)

Number of websites (real‑time counter at internetlivestats.com)

Web Page Sizes: A (Not So) Brief History of Page Size through 2015

Further Reading

Martin Fowler’s Microservices Resource Guide

Chris Richardson’s Microservice architecture patterns and best practices

NGINX, Inc. blog posts:

- Inside NGINX: How We Designed for Performance & Scale

- HTTP Keepalive Connections and Web Performance

- Facing the Hordes on Black Friday and Cyber Monday

- Building a Great App Is Just the Beginning; How Do You Deliver It at Scale?

- 12 Reasons Why NGINX is the Standard for Containerized Applications and Deploying Microservices

- Chris Richardson’s seven-part series on microservices (also published as an ebook, Microservices: From Design to Deployment)

- Adopting Microservices at Netflix: Lessons for Architectural Design