Support for HTTP/2 server push is also included in NGINX Plus R15.

We’re delighted to announce that NGINX 1.13.9, released on February 20, 2018, includes support for HTTP/2 server push. For NGINX Plus users, HTTP/2 server push support will be included in the upcoming NGINX Plus R15 release, scheduled for April 2018.

Server push, which is defined in the HTTP/2 specification, allows a server to pre‑emptively push resources to a remote client, anticipating that the client may soon request those resources. By doing so, you can potentially reduce the number of RTTs (round trip time – the time needed for a request and response) in a page‑load operation by one RTT or more, providing faster response to the user.

Server push can be used to prime a client with style sheets, images, and other resources that it will need to render a web page. You should take care to only push resources that are required; don’t push resources that a client is likely to already have cached.

In this blog post, I describe:

- Basic configuration for HTTP/2 server push

- How to verify that HTTP/2 server push is working (using browser tools or

nghttp) - Automatically pushing content using the

Linkheader - Selectively pushing content

- Measuring the effect of HTTP/2 server push

Configuring HTTP/2 Server Push

To push resources along with a page load, use the http2_push directive as follows:

server {

# Ensure that HTTP/2 is enabled for the server

listen 443 ssl http2;

ssl_certificate ssl/certificate.pem;

ssl_certificate_key ssl/key.pem;

root /var/www/html;

# whenever a client requests demo.html, also push

# /style.css, /image1.jpg and /image2.jpg

location = /demo.html {

http2_push /style.css;

http2_push /image1.jpg;

http2_push /image2.jpg;

}

}

Verifying HTTP/2 Server Push

You can easily verify that server push is in effect using either of two methods:

- The developer tools in your web browser

- A command‑line HTTP/2 client such as

nghttp

Verifying with Developer Tools (Google Chrome)

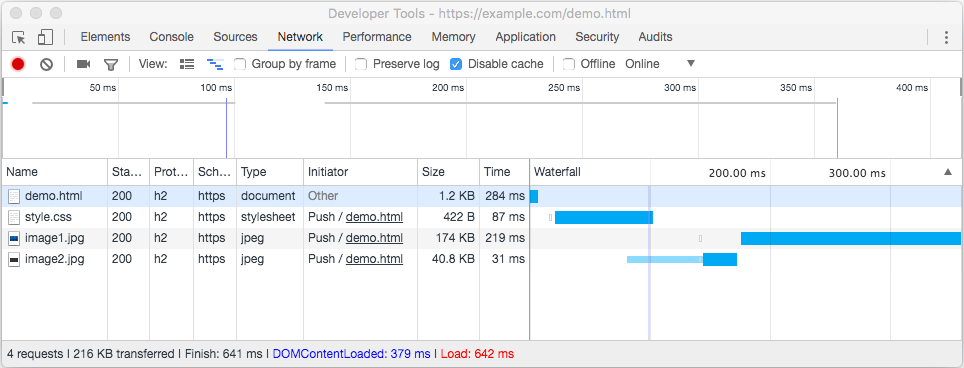

Here’s how to use the developer tools in your web browser to verify that server push is in effect, using Google Chrome as an example. In the figure, the Initiator column on the Network tab of Chrome’s Developer Tools indicates that several resources were pushed to the client as part of a request for /demo.html.

Verifying with a Command-Line Client (nghttp)

In addition to web browser tools, you can use the nghttp command‑line client from the nghttp2.org project to verify that server push is in effect. You can download the nghttp command‑line client from GitHub, or install the appropriate operating system package where available. For Ubuntu, use the nghttp2-client package.

In the output, the asterisk (*) marks resources that were pushed by the server.

$ nghttp -ans https://example.com/demo.html

id responseEnd requestStart process code size request path

13 +84.25ms +136us 84.11ms 200 492 /demo.html

2 +84.33ms * +84.09ms 246us 200 266 /style.css

4 +261.94ms * +84.12ms 177.83ms 200 40K /image2.jpg

6 +685.95ms * +84.12ms 601.82ms 200 173K /image1.jpgAutomatically Pushing Resources to Clients

In many situations, it’s inconvenient – or even impossible – to list the resources you wish to push in the NGINX configuration file. For this reason, NGINX also supports the convention of intercepting Link preload headers, then pushing the resources identified in these headers. To enable preload, include the http2_push_preload directive in the configuration:

server {

# Ensure that HTTP/2 is enabled for the server

listen 443 ssl http2;

ssl_certificate ssl/certificate.pem;

ssl_certificate_key ssl/key.pem;

root /var/www/html;

# Intercept Link header and initiate requested Pushes

location = /myapp {

proxy_pass http://upstream;

http2_push_preload on;

}

}

For example, when NGINX is operating as a proxy (for HTTP, FastCGI, or other traffic types), the upstream server can add a Link header like this to its response:

Link: </style.css>; as=style; rel=preloadNGINX intercepts this header and commences a server push of /style.css. The path in the Link header must be absolute – relative paths like ./style.css are not supported. The path can optionally include a query string.

To push multiple objects, you can provide multiple Link headers, or, better still, include all objects in a comma‑separated list:

Link: </style.css>; as=style; rel=preload, </favicon.ico>; as=image; rel=preloadIf you don’t want NGINX to push a preloaded resource, add the nopush parameter to the header:

# Resource is not pushed

Link: </nginx.png>; as=image; rel=preload; nopushWhen http2_push_preload is enabled, you can also initiate preload server push by setting the response header in your NGINX configuration:

add_header Link "</style.css>; as=style; rel=preload";Selectively Pushing Resources to Clients

The HTTP/2 specification doesn’t address the challenge of determining whether or not to push resources. Clearly, it’s best to push only resources to clients if you know both that they are likely to need the resource and that it’s unlikely they already have it cached.

One possible approach is to push resources to clients only on their first visit to the site. You can test for the presence of a session cookie, for example, and set the Link header conditionally, so the resources are preloaded only if the session cookie is not present.

Assuming clients are well‑behaved and include the cookie in subsequent requests, with the following configuration NGINX pushes the resources to the clients only once per browser session:

server {

listen 443 ssl http2 default_server;

ssl_certificate ssl/certificate.pem;

ssl_certificate_key ssl/key.pem;

root /var/www/html;

http2_push_preload on;

location = /demo.html {

add_header Set-Cookie "session=1";

add_header Link $resources;

}

}

map $http_cookie $resources {

"~*session=1" "";

default "</style.css>; as=style; rel=preload, </image1.jpg>; as=image; rel=preload, </image2.jpg>; as=image; rel=preload";

}Measuring the Effect of HTTP/2 Server Push

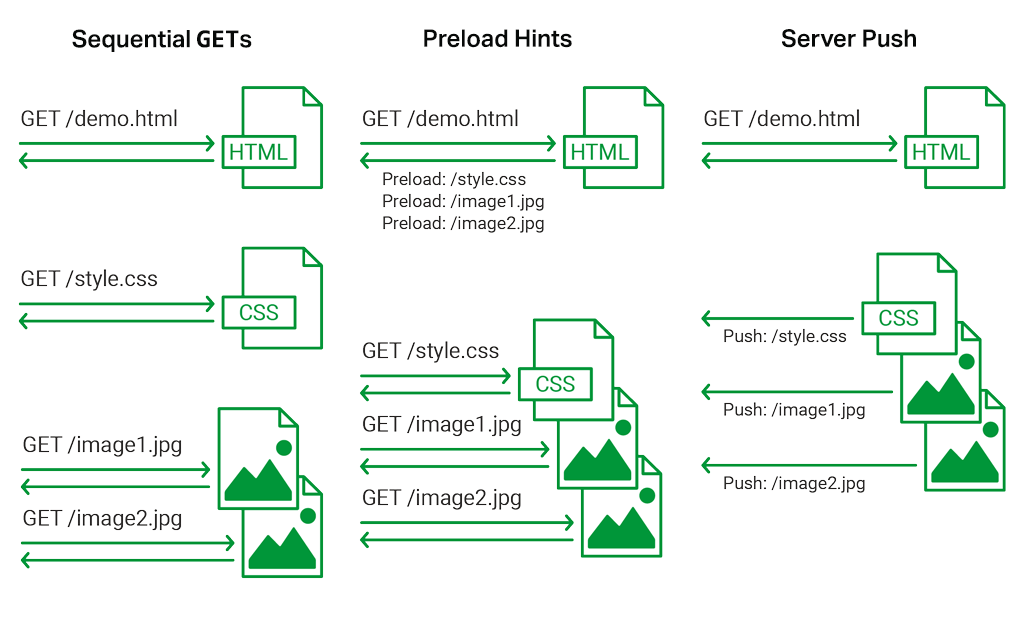

To measure the effect of server push, we created a simple test page, /demo.html, that references a separate stylesheet, /style.css. The stylesheet further references two images. We tested page‑load times using three different configurations:

- Sequential

GETs (No optimization) – The browser loaded resources when it discovered they were required - Preload Hints – Preload hints (

Linkheaders) were included in the first response to tell the browser to load the dependencies - Server Push (HTTP/2 only) – Dependencies were pre‑emptively pushed to the browser

We did multiple test runs of each configuration using HTTP, HTTPS, or HTTP/2. The first two configurations apply to all three protocols, and server push only to HTTP/2.

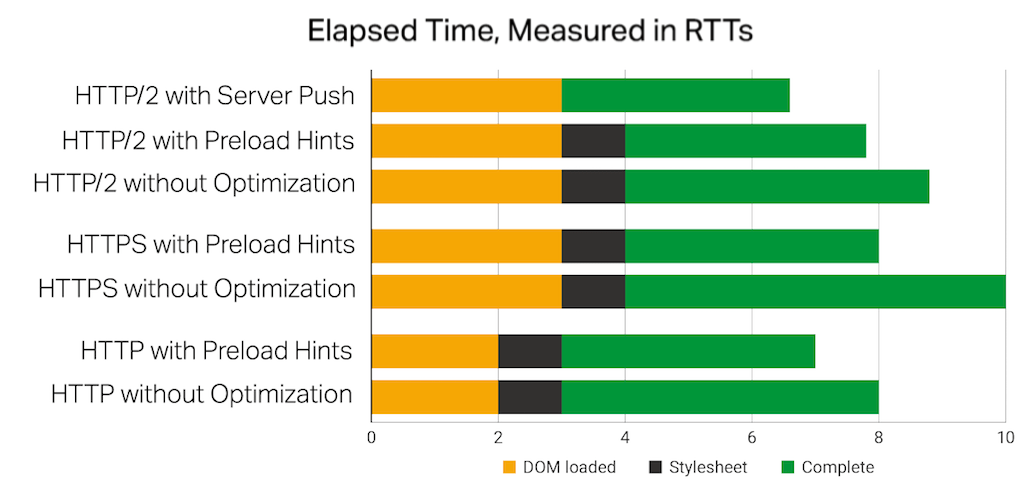

The behavior was measured using the Chrome developer tools. The most common behavior of each configuration was assessed and averaged, and the times were correlated with the RTT of the link (as measured using ping) to illustrate the mechanical effect of each method.

Some Basic Observations

- DOM loaded is the time to initiate a new connection and retrieve the demo.html page. Stylesheet is the time to retrieve the CSS resource.

- Establishing a connection over HTTP takes 1 RTT; for HTTPS and HTTP/2, it takes 2 RTTs.

- The payload for the HTML and CSS resources is smaller than the maximum transmission unit (MTU) size, so a

GEToperation completes in approximately 1 RTT.

Interpreting the Results: Preload Hints

- Preload hints have minimal effect for the CSS resource because it is directly referenced within the HTML resource, and the HTML resource is delivered quickly. The browser initiates the CSS request as soon as the HTML page is delivered.

- Preload hints do have the effect of quickly starting the download of resources that are declared in the CSS resource (here, the two images). The downloads can start 1 RTT faster when preload hints are used.

- The net savings from preload hints can be 1 RTT or more. When downloading resources in parallel, the browser must open one or more additional connections. Performance depends on whether slow requests (larger responses) are scheduled first, or are delayed while new connections are opened. This unpredictable request ordering accounts for the 1‑RTT speedup for HTTP and HTTP/2, and the 2‑RTT speedup for HTTPS.

Interpreting the Results: Server Push

- Server push improved on the preload‑hints time by a further 1 RTT. The push “responses” were initiated at the same time as the response to the first request, whereas the preload‑hints responses incurred 1 RTT delay – 0.5 RTT for the response to the first request plus 0.5 RTT for the preload

GETrequest.

Test Notes

- There were multiple test runs for each configuration. Each run began with an empty browser cache and with no established keepalive connections to the NGINX server. The NGINX directives

keepalive_timeoutandhttp2_idle_timeoutwere used to quickly close keepalive connections. - It currently does not appear possible to push font resources to Chrome, perhaps due to a known complication. Chrome makes an explicit request for a font resource even it it has already been pushed.

- Care was taken to explicitly clear browser caches before each test, and all content was served with expired cache control headers.

- Chrome caches preloaded resources. These cached resources are not consistently ignored when you disable caching, and are not consistently cleared by an explicit “clear browser cache” operation. (In Chrome, one way to disable caching is to check the Disable cache checkbox on the Developer Tools Network tab. To clear the browser cache, you can right‑click the browser refresh button with Developer Tools open and select Empty Cache and Hard Reload).

- Some attempts to preload content caused Chrome to unsuccessfully revalidate cached copies, then download the resource normally. These attempts were not counted in the measurements.

- Chrome adds an unnecessary 2‑RTT delay to all new SSL connections that use previously accepted self‑signed certificates. The test was conducted using CA‑signed Let’s Encrypt certificates to avoid this 2‑RTT delay.

- DNS delays were addressed by editing the local /etc/hosts file.

- These simple tests did not attempt to measure the effect of server push when the client already has a cached copy of the resource. In the tests, all caches were cleared before each test, and most pushes were too quick to cancel.

Conclusion

This test was deliberately simple, in order to highlight the mechanics of preload hints and server push. Server push delivers a 1‑RTT improvement over preload hints in simple situations, and a greater improvement compared to unoptimized, sequential GET requests and discovery of dependent resources.

More realistic use cases have a great many more variables: multiple dependent resources, multiple sources, even the possibility of wasted bandwidth by pushing resources that are already cached or not immediately needed. Browser inconsistencies also affect performance. Your mileage will certainly vary from this simple test.

For example, the Chrome team has published some detailed recommendations on when to deploy server push, and has taken measurements on more complex sites to compare the effects of no optimization, preload hints, and server push over HTTP/2. Their Rules of Thumb for HTTP/2 Push report is worth reading for anyone considering deploying HTTP/2 server push in production.

The pragmatic conclusion is that if you can identify which resources are required in advance, there’s real benefit in having upstream servers send a preload hint. The additional benefit of pushing these resources is small but measurable, but may possibly result in wasted bandwidth and delays for needed resources. You should test and monitor any server‑push configurations carefully.

Appendix: How Does HTTP/2 Push Work?

The information below is based in part on the research in Jake Archibald’s very detailed HTTP/2 push is tougher than I thought blog post.

HTTP/2 server push is typically used to send dependent resources preemptively when the client requests a resource. For example, if a client requests a web page, the server may push dependent stylesheets, fonts, and images to the client.

When a client makes an HTTP/2 connection, the server can chose to initiate one or more server‑push responses over the connection. These pushes send resources that the client has not explicitly requested.

The client can either reject a push (by sending an RST_STREAM frame) or accept it. The client stores the pushed content in a local “push cache” that is associated with the HTTP/2 connection.

Later, when the client makes a request for a resource using an established HTTP/2 connection, it checks the connection’s push cache for a completed or in‑transit response to the request. It uses the cached resource in preference to making a new HTTP/2 request for the resource.

Any pushed resource remains in the per‑connection push cache until (a) it is used or (b) the HTTP/2 connection is closed:

- If the resource is used, the client takes a copy and the entry in the push cache is deleted. If the resource is cacheable, the client can then cache its copy in its HTTP page cache.

- If the HTTP/2 connection is closed for any reason, its local push cache is deleted.

This has several implications:

- Content in the HTTP page cache in the browser is used in preference to content in the push cache, even if the pushed content is fresher.

- HTTP/2 connections can be shared among different page loads. A resource that is pushed as a result of one page load can be used when requested in a different page load.

- Requests with credentials use different HTTP/2 connections from requests without credentials; for example, a resource that is pushed with a cross‑origin request (credentialed) might not be found if the browser makes a non‑credentialed request for the resource.

You can review a much more detailed list of issues in Jake Archibald’s HTTP/2 push is tougher than I thought blog post.

HTTP/2 server push is an interesting capability. Make sure to thoroughly test your HTTP/2 server push configuration, and be prepared to fall back to preload hints in cases where this gives more predictable, cache‑aware behaviour.