In a previous blog post, we shared best practices for designing a microservices architecture, based on Adrian Cockcroft’s presentation at nginx.conf 2014 about his experience as Director of Web Engineering and then Cloud Architect at Netflix. In this follow‑up post, we’ll review his recommendations for retooling your development team and processes for a smooth transition to microservices.

Optimize for Speed, not Efficiency

The top lesson that Cockcroft learned at Netflix is that speed wins in the marketplace. If you ask developers whether a slower development process is better, no one ever says yes. Nor do management or customers ever complain that your development cycle is too fast for them. The need for speed doesn’t just apply to tech companies, either: as software becomes increasingly ubiquitous on the Internet of Things – in cars, appliances, and sensors as well as mobile devices – companies that didn’t used to do software development at all now find that their success depends on being good at it.

Netflix made an early decision to optimize for speed. This refers specifically to tooling your software development process so that you can react quickly to what your customers want, or even better, can create innovative web experiences that attract customers. Speed means learning about your customers and giving them what they want at a faster pace than your competitors. By the time competitors are ready to challenge you in a specific way, you’ve moved on to the next set of improvements.

This approach turns the usual paradigm of optimizing for efficiency on its head. Efficiency generally means trying to control the overall flow of the development process to eliminate duplication of effort and avoid mistakes, with an eye to keeping costs down. The common result is that you end up focusing on savings instead of looking for opportunities that increase revenue.

In Cockcroft’s experience, if you say “I’m doing this because it’s more efficient”, the unintended result is that you’re slowing someone else down. This is not an encouragement to be wasteful, but you should optimize for speed first. Efficiency becomes secondary as you satisfy the constraint that you’re not slowing things down. The way you grow the business to be more efficient is to go faster.

Make Sure Your Assumptions are Still True

Many large companies that have enjoyed success in their market (we can call them incumbents) are finding themselves overtaken by nimbler, usually smaller, organizations (disruptors) that react much more quickly to changes in consumer behavior. Their large size isn’t necessarily the root of the problem – Netflix is no longer a small company, for example. As Cockcroft sees it, the main cause of difficulty for industry incumbents is that they’re operating under business assumptions that are no longer true. Or, as Will Rogers put it,

Of course, you have to make assumptions as you formulate a business model, and then it makes sense to optimize your business practices around them. The danger comes from sticking with assumptions after they’re no longer true, which means you’re optimizing on the wrong thing. That’s when you become vulnerable to industry disruptors who are making the right assumptions and optimizations for the current business climate.

As examples, consider the following assumptions that hold sway at many incumbents. We’ll examine them further in the indicated sections and describe the approach Netflix adopted.

- Computing power is expensive. This was true when increasing your computing capacity required capital expenditure on computer hardware. See Put Your Infrastructure in the Cloud.

- Process prevents problems. At many companies, the standard response to something going wrong is to add a preventative step to the relevant procedure. See Create a High‑Freedom, High‑Responsibility Culture with Less Process.

Here are some ways to avoid holding onto assumptions that have passed their expiration date:

- As obvious as it might seem, you need to make your assumptions explicit, then periodically review them to make sure they still hold true.

-

Keep aware of technological trends. As an example, the cost of solid‑state drive (SSD) storage continues to go down. It’s still more expensive than regular disks, but the cost difference is becoming small enough that many companies are deciding the superior performance is worth paying a bit more for.

[Editor – In this entertaining video, Fastly founder and CEO Artur Bergman explains why he believes SSDs are always the right choice.]

- Talk to people who aren’t your customers. This is especially necessary for incumbents, who need to make sure that potential new customers are interested in their product. Otherwise, they don’t hear about the fact that they’re not being used. As an example, some vendors in the storage space are building hyper‑converged systems even as more and more companies are storing their data in the cloud and using open source storage management software. Netflix, for example, stores data on Amazon Web Services (AWS) servers with SSDs and manages it with Apache Cassandra. A single specialist in Java distributed systems is managing the entire configuration without any commercial storage tools or help from engineers specializing in storage, SAN, or backup.

- Don’t base your future strategy on current IT spending, but instead on level of adoption by developers. Suppose that your company accounts for nearly all spending in the market for proprietary virtualization software, but then a competitor starts offering an open source‑based product at only 1% the cost of yours. If people start choosing it instead of your product, then at the point that your share of total spending is still 90%, your market share has declined to only 10%. If you’re only attending to your revenue, it seems like you’re still in good shape, but 10% of market share can collapse really quickly.

Put Your Infrastructure in the Cloud

We previously mentioned that in the past it was valid to base your business plan on the assumption that computing power was expensive, because it was: the only way to increase your computing capacity was to buy computer hardware. You could then make money by using this expensive resource in the right way to solve customer problems.

The advent of cloud computing has pretty much completely invalidated this assumption. It is now possible to buy the amount of capacity you need when you need it, and to pay for only the time you actually use it. The new assumption you need to make is that (virtual) machines are ephemeral. You can create and destroy them at the touch of a button or a call to an API, without any need to negotiate with other departments in your company.

One way to think of this change is that the self‑service cloud makes formerly impossible things instantaneous. All of Netflix’s engineers are in California, but they manage a worldwide infrastructure. The cloud enables them to experiment and determine whether (for example) adding servers in particular location improves performance. Suppose they notice problems with video delivery in Brazil. They can easily set up 100 cloud server instances in São Paulo within a couple hours. If after a week they determine that the difference in delivery speed and reliability isn’t large enough to justify the cost of the additional server instances, they can shut them down just as quickly and easily as they created them.

This kind of experiment would be so expensive with a traditional infrastructure that you would never attempt it. You would have to hire an agent in São Paulo to coordinate the project, find a data center, satisfy Brazilian government regulations, ship machines to Brazil, and so on. It would be six months before you could even run the test and find out that increased local capacity didn’t improve your delivery speed.

Create a High‑Freedom, High‑Responsibility Culture with Less Process

We previously observed that many companies create rules and processes to prevent problems. When someone makes a mistake, they add a rule to the HR manual that says “well, don’t do that again”. If you read some HR manuals from this perspective, you can extract a historical record of everything that went wrong at the company. When something goes wrong in the development process, the corresponding reaction is to add a new step to the procedure. The major problem with creating process to prevent problems is that over time you build up complex “scar tissue” processes that slow you down.

Netflix doesn’t have an HR manual. There is a single guideline: “Act in Netflix’s best interest”. The idea is that if an employee can’t figure out how to interpret the guideline in a given situation, he or she doesn’t have enough judgment to work there. If you don’t trust the judgment of the people on your team, you have to ask why you’re employing them. It’s true that you’ll have to fire people occasionally for violating the guideline. Overall, the high level of mutual trust among members of a team, and across the company as a whole, becomes a strong binding force.

The following books outline new ways of thinking about process if you’re looking to transform your organization:

- The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox. This book has become a standard management text at business schools since its original publication in 1984. Written as a novel about a manager who has only 90 days to improve performance at his factory or have it closed down, it embodies Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints in the context of process control and automation.

- The Phoenix Project: A Novel about IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win by Gene Kim and Kevin Behr. As the title indicates, it’s also a novel, about an IT manager who has 90 days to save a project that’s late and over budget, or his entire department will be outsourced. He discovers DevOps as the solution to his problem.

Replace Silos with Microservices Teams

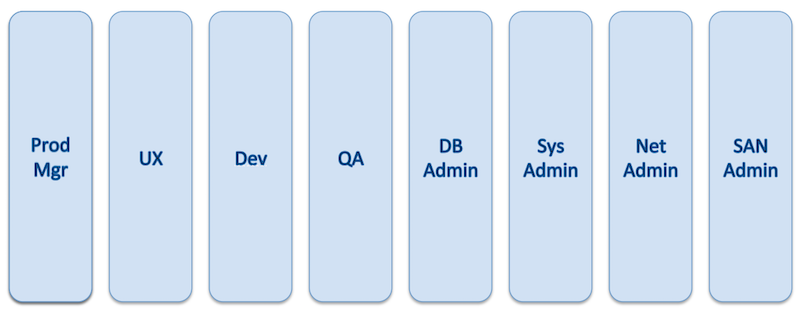

Most software development groups are separated into silos, with no overlap of personnel between them. The standard process for a software development project starts with the product manager meeting with the user‑experience and development groups to discuss ideas for new features. After the idea is implemented in code, the code is passed to the quality assurance (QA) and database administration teams and discussed in more meetings. Communication with the system, network, and SAN administrators is often via tickets. The whole process tends to be slow and loaded with overhead.

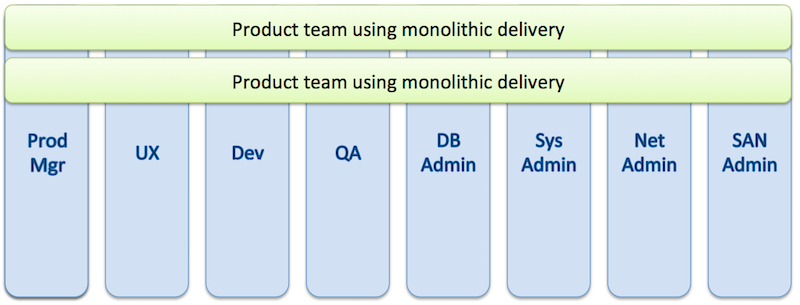

Some companies try to speed up by creating small “startup”‑style teams that handle the development process from end to end, or sometimes such teams are the result of acquisitions where the acquired company continues to run independently as a separate division. But if the small teams are still doing monolithic delivery, there are usually still handoffs between individuals or groups with responsibility for different functions. The process suffers from the same problems as monolithic delivery in larger companies – it’s simply not very efficient or agile.

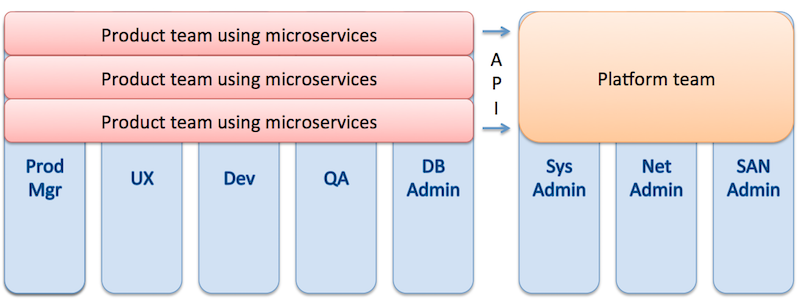

Conway’s law says that the interface structure of a software system reflects the social structure of the organization that produced it. So if you want to switch to a microservices architecture, you need to organize your staff into product teams and use DevOps methodology. There are no longer distinct product managers, UX managers, development managers, and so on, managing downward in their silos. There is a manager for each product feature (implemented as a microservice), who supervises a team that handles all aspects of software development for the microservice, from conception through deployment. The platform team provides infrastructure support that the product teams access via APIs. At Netflix, the platform team was mostly AWS in Seattle, with some Netflix‑managed infrastructure layers built on top. But it doesn’t matter whether your cloud platform is in‑house or public; the important thing is that it’s API‑driven, self‑service, and automatable.

Adopt Continuous Delivery, Guided by the OODA Loop

A siloed team organization is usually paired with monolithic delivery model, in which an integrated, multifunction application is released as a unit (often version‑numbered) on a regular schedule. Most software development teams use this model initially because it is relatively simple and works well enough with a small number of developers (say, 50 or fewer). However, as the team grows it becomes a real issue when you discover a bug in one developer’s code during QA or production testing and the work of 99 other developers is blocked from release until the bug is fixed.

In 2009 Netflix adopted a continuous delivery model, which meshes perfectly with a microservices architecture. Each microservice represents a single product feature that can be updated independently of the other microservices and on its own schedule. Discovering a bug in a microservice has no effect on the release schedule of any other microservice. Continuous delivery relies on packaging microservices in standard containers. Netflix initially used Amazon machine images (AMIs) and it was possible to deploy an update into a test or production environment in about 10 minutes. With Docker, that time is reduced even further, to mere seconds in some cases.

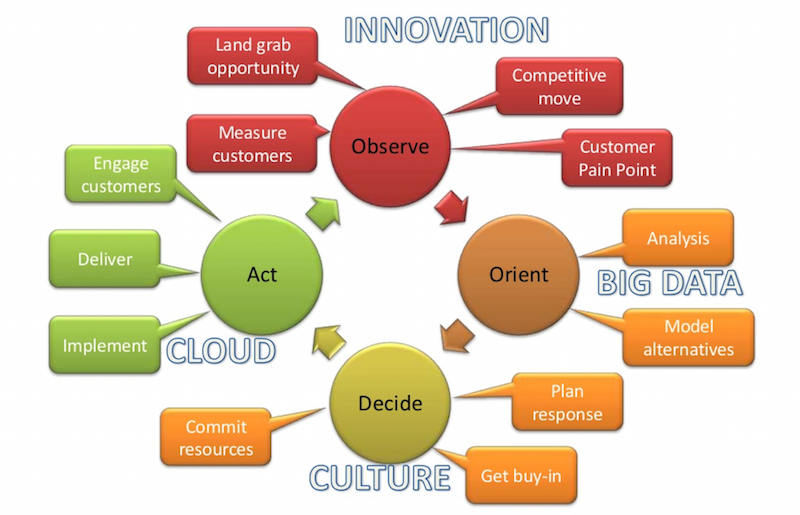

At Netflix, the conceptual framework for continuous development and delivery is an Observe‑Orient‑Decide‑Act (OODA) loop.

Observe refers to examining your current status to look for places where you can innovate. You want your company culture to implicitly authorize anyone who notices an opportunity to start a project to exploit it. For example, you might notice what the diagram calls a “customer pain point”: a lot of people abandoning the registration process on your website when they reach a certain step. You can undertake a project to investigate why and fix the problem.

Orient refers to analyzing metrics to understand the reasons for the phenomena you’ve observed at the Observe point. Often this involves analyzing large amounts of unstructured data, such as log files; this is often referred to as big data analysis. The answers you’re looking for are not already in your business intelligence database. You’re examining data that no one has previously looked at and asking questions that haven’t been asked before.

Decide refers to developing and executing a project plan. Company culture is a big factor at this point. As previously discussed, in a high‑freedom, high‑responsibility culture you don’t need to get management approval before starting to make changes. You share your plan, but you don’t have to ask for permission.

Act refers to testing your solution and putting it into production. You deploy a microservice that includes your incremental feature to a cloud environment, where it’s automatically put into an A/B test to compare it to the previous solution, side by side, for as long as it takes to collect the data that shows whether your approach is better. Cooperating microservices aren’t disrupted, and customers don’t see your changes unless they’re selected for the test. If your solution is better, you deploy it into production. It doesn’t have to be a big improvement, either. If the number of clients for your microservice is large enough, then even a fraction of a percent improvement (in response time, say) can be shown to be statistically valid, and the cumulative effect over time of many small changes can be significant.

Now you’re back at the Observe point. You don’t always have to perform all the steps or do them in strict order, either. The important characteristic of the process is that it enables you quickly to determine what your customers want and to create it for them. Cockcroft says “it’s hard not to win” if you’re basing your moves on enough data points and your competitors are making guesses that take months to be proven or disproven.

The state of art is to circle the loop every one to two weeks, but every microservice team can do it independently. With microservices you can go much faster because you’re not trying to get the entire company going around the loop in lockstep.

How NGINX Plus Can Help

At NGINX we believe it’s crucial to your future success that you adopt a four‑tier application architecture in which applications are developed and deployed as sets of microservices. We hope the information we’ve shared in this post and its predecessor, Adopting Microservices at Netflix: Lessons for Architectural Design, are helpful as you plan your transition to today’s state‑of‑the‑art architecture for application development.

When it’s time to deliver your apps, NGINX Plus offers an application delivery platform that provides the superior performance, reliability, and scalability your users expect. Fully adopting a microservices‑based architecture is easier and more likely to succeed when you move to a single software tool for web serving, load balancing, and content caching. NGINX Plus combines those functions and more in one easy to deploy and manage package. Our approach empowers developers to define and control the flawless delivery of their microservices, while respecting the standards and best practices put into place by a platform team. Click here to learn more about how NGINX Plus can help your applications succeed.